ARTO: OK, so tell us about your music idea.

MJS: The whole music idea comes from a psychological perspective on what happened to Chile during those years. So here’s the situation: The country is divided and people are not talking about the issue at hand, which is that something happened to us on Tuesday, 9 a.m., Sept. 11, 1973. Nobody talks because they’d get into a fight. Once I moved here, I thought about trauma, what happens when a human being suffers a traumatic event – the self splits, dissociates. The identity is broken sometimes to the point where you don’t know who you are. So I was reflecting that I grew up listening to the radio broadcasts, complaining that Chileans have no identity! For instance, Brazilian people have the carnival and are gods at football, the French kiss like heaven and eat baguettes. But Chileans, we just don’t know what a Chilean does. In terms of theory, something I’m working on personally is the concept of a nation being able to have an identity itself. This identity that should be ingrained in each of us was split. The cure to that split is the integration of identity into a common narrative that makes sense.

As a nation, in Chile, we have a narrative problem. A healthy person can tell a story connecting their life from say two, three, four years old all the way through to their life at present. We can’t do that for our country. We can't make a continuous story. We know that in 1520 Magellan navigated the Straits named after him. We know that Santiago was founded in 1541. We know a number of things, we can talk about Chilean history, but only up until 9/11/73. 30 years later, as I mentioned, some films are now being done. Machuca is another one I saw recently. It's about the military coup. However, I still can’t have a conversation with my own father about it.

ARTO: So there is no story line and an incapacity to define who Chileans are.

MJS: Yes. One of the big things in trauma is apology, acknowledgment. There have been attempts in Chile to integrate but they have not been sufficient because the trauma itself has not fully been acknowledged. The military has not asked for forgiveness. There has not been enough acknowledgment of the victims. It is very hard to reach integration if those basic parts are not there. It would be great if the whole nation of Chile would get really angry at the CIA. That would really serve the nation. Argentina, on the other hand, another country that had to deal with a similarly oppressive dictatorship, they have an easier time with knowing who they are. One reason, I think, is that the military apologized to the victims.

ARTO: That attests to the power of the Truth and Reconciliation process, which got a foothold in Argentina. Not so much in Chile?

MJS: Right. Chile is still filled with people who lost their dear ones and never had a chance to say goodbye. No idea where they ended up. The way you can kill someone twice is by not acknowledging their death. Actuallly, I find a lot of parallels between what happened in Chile and the story of Jesus when he was crucified. The Roman Empire would kill people in a way that would erase their memory. No funeral, no grave.

ARTO: Which would be especially important with someone who was considered a powerful, radical, champion of social justice.

MJS:In Chile, the family members of the disappeared had their memories taken away; dishonored. There hasn’t been a funeral. The country has not been able to return the memories to them. I grieve that I have no place to grieve.

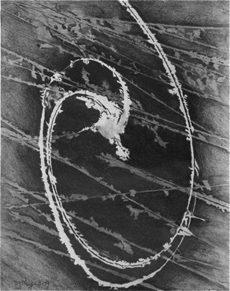

So we have a group of people who have lost dear ones, and a major segment of the population who cannot connect with that pain because it is not written in history. The Gospels were written as a way to keep Jesus from being permanently “disappeared,” in spite of the efforts of the Romans. Similarly, we need a way to tell the story of our oppressed. A good way to tell any history is on the level of art. Art is powerful because you can’t argue against it, or even for it, on a factual level. It’s just there and can’t be denied.

ARTO: That makes me think of Karl Morrison, who wrote about the philosophical tradition of "radical empathy." He speaks to that. He said that the power of empathy is its "affective logic," a kind of knowing deeper than the ideological sort, that's capable of resisting propositional assault or ridicule. The whole gestalt or experience of art fits into that schema as well. Perhaps you see your art idea as a bridge that moves the depth of people into closer proximity.

MJS: Yes. In essence, if I make art to honor these people, someone like my dad cannot refute the feelings that we've been left with because of our disappeared history, with his arguments about how "communism doesn't work."

So I have this concern about this void in my country’s history, and about the younger generation and about some of my own friends who don’t give a damn. What’s a way that I can humbly care for those people? I want to introduce them to the artists I’ve discovered from the Pinochet era, the artists whose voices were silenced at the time. Maybe now is when we really need them, to help us reclaim part of our lost identity.

ARTO: Artists such as?

MJS: Violetta Parra, who was a musician and multimedia artist; Victor Jara was a songwriter. I only learned his story once I moved to the USA. He was a protest singer like Bob Dylan. Victor Jara would sing about class struggle, so when the military coup took place he was taken with many other people to a sports stadium that was used as a concentration camp.

The legend goes that he was playing his guitar, songs of freedom. Soldiers came and told him to shut up. He refused. The soldiers cut his hands off, and he died singing, that’s how the legend goes. Now that stadium is called Victor Jara Stadium.

So I want to produce and sing songs by Victor Jara and Violetta Parra, and other Chilean songs, with contemporary indie-rock arrangements, with some of the great musicians I've come to know here in Seattle.

ARTO: Why update the music into contemporary indie-rock arrangements?

MJS: I want to appeal to the younger generation of Chileans. A lot of them are part of a movement, or more of an anti-movement, called Pokemons. That's what they call themselves. They gather in large groups and try to kiss and grope as many other Pokemons as they can. They are all about dressing a certain way and they are very blatant about avoiding connecting to anything serious or meaningful.

ARTO: So, you are trying to offer these Pokemons an option to have identity or cultural forms that actually relate to something Chilean. Here they are, naming themselves after a Japanese game. But you're saying, "There's something right here for you— you just didn't know about it."

MJS: Yes, I want the Pokemons and the other people who have disconnected from the emotional reality of our history to know that their country can be a great country and it’s up to them to make it the great country it has been.

ARTO: You mention the musical community you've found in Seattle. How has living in the United States affected your identity as a musician and artist?

MJS: I say I became more Chilean after coming to the US. I started writing songs here and they all sounded very South American. I am just now growing a taste for South American music. I grew up listening to Pop and Rock – English music – and that’s how I learned English. But anything I play sounds South American – I can’t help it! And this was never my music of choice. Same with my artwork. People in the US who have seen my paintings could recognize elements that were very specifically South American – something I had no conscious knowledge of before.

And there are other projects I want to do that revolve around the same impulses. I would love to gather the stories of people in Chile about that period. Not only the survivors of the disappeared, but also including the people who had to wipe their butts with newspapers, like my parents... any way I can help my country get more connected to this dark part of our history and begin healing and reintegrating as individuals and as a culture.

ARTO: Do yo have any fear about beginning to tell these stories among your fellow Chileans?

MJS: As of today, I know I will be dismissed. In totalitarian Berlin people were afraid to talk, but they would in secret. In Chile today, they are free to talk about it but they don’t want to.